The Boeing Boom elevated the Seattle area’s black homeowners. The tech boom? Just the opposite, as the region’s rate of homeownership ranks among the lowest in the country.

Share story

Homeownership — it’s the cornerstone of the American dream.

In recent years, with prices soaring out of reach, that dream seems more like a nightmare to many would-be Seattle homebuyers.

But for black families in King County, it’s old news. The dream of homeownership is one that’s been slipping away for decades.

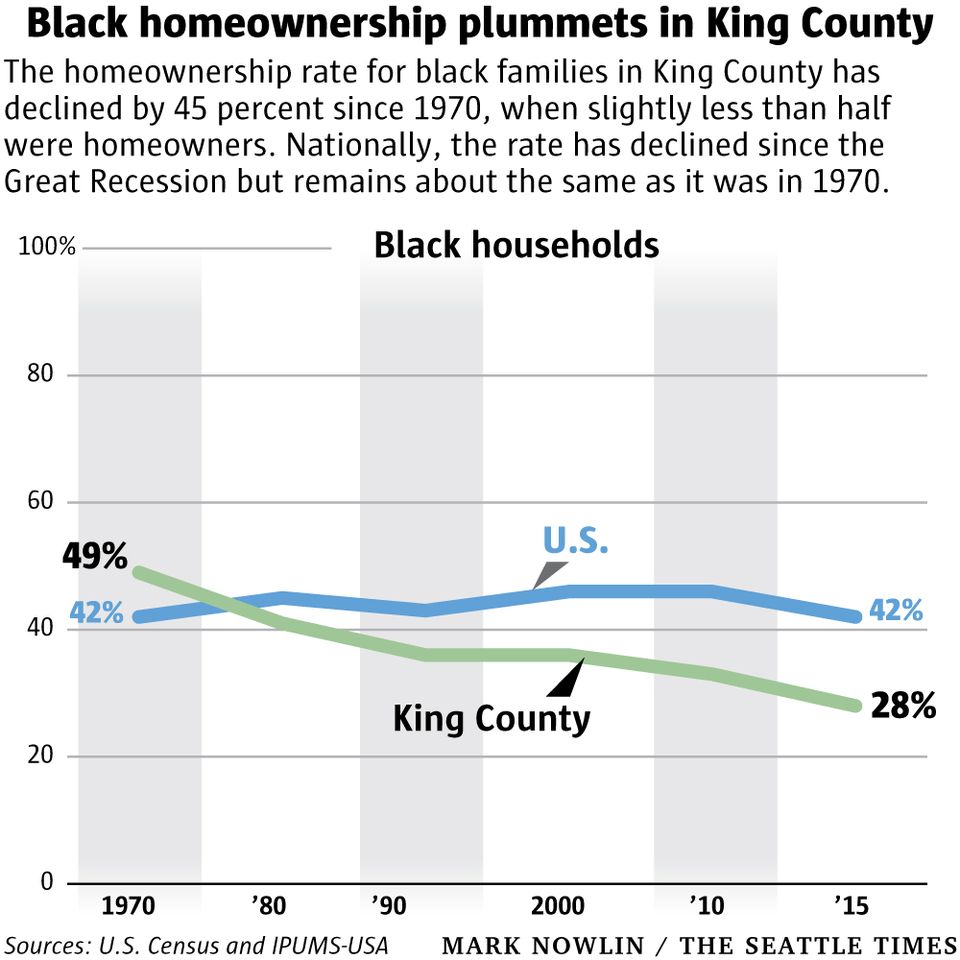

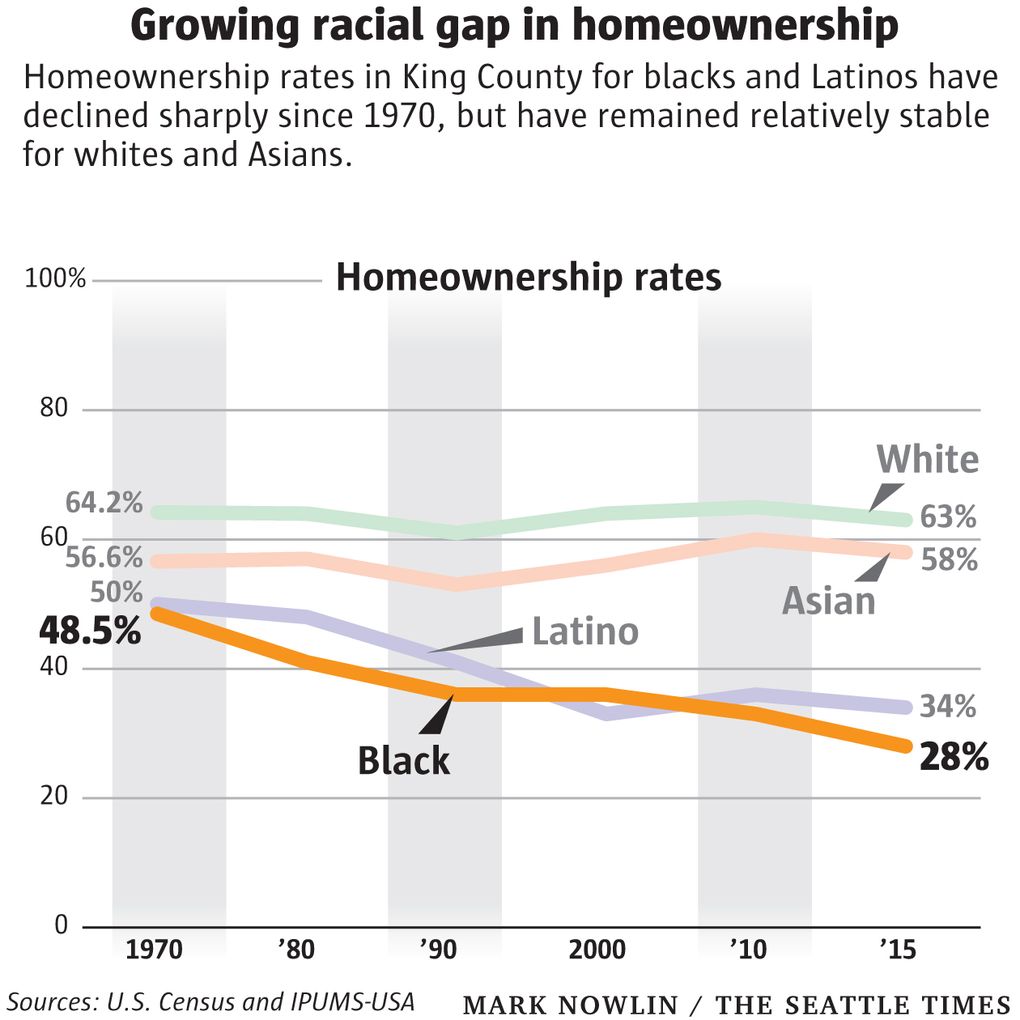

In 1970, almost half of King County households headed by a black person owned their home, according to census data. The rate of black homeownership here, at 49 percent, was well above the U.S. average of 42 percent.

Since then, black homeownership in King County has been on a steady downward spiral, with just 28 percent of black households in the county owning their home — about 13,000 of the nearly 48,000 total households.

Homeownership for Latinos has also declined sharply since 1970, but has remained relatively stable for whites and Asians.

What’s happened here for black homeowners does not parallel a wider trend. Nationally, 42 percent of black households own their home, the same as in 1970. King County, once well above average for black homeownership, is now far below. While a racial-affordability gap exists in housing markets across the country, it is more extreme here than in most places.

It’s a sign of how the postwar Boeing Boom was, in many ways, more beneficial to Seattle’s black community than the current tech boom, says Ron Sims, former deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, who also served as the King County Executive.

“African Americans have not done well in the economy of King County and the Puget Sound, as Boeing has moved jobs elsewhere,” he said.

“I’ll be blunt about it: The tech sector has failed to provide open doors and equal pay to African Americans. And they’ve acknowledged it.”

According to the most recent census data, less than 2 percent of King County residents who work in tech jobs are black. That’s about 1,500 people.

Compare that with the period after World War II, when tens of thousands of blacks moved to this area for high-paying jobs, primarily at Boeing. By the early 1950s, the median income for black households in Seattle was just 1 percent lower than the U.S. median for whites.

In the present census data, it’s 48 percent lower.

It’s not that blacks didn’t face obstacles on the path to homeownership in Seattle’s postwar period. There was the insidious practice of redlining by banks, and many city neighborhoods had racial-restrictive covenants. While some of these institutional barriers are gone, the economic barriers that now exist seem even more insurmountable.

“You have escalating housing prices in King County,” Sims said, “and, over time, African Americans have not been able to access that market.”

Gary Hammon recalls that time when homeownership didn’t seem so out of reach. Hammon, a jazz musician and educator, lives in the Central District house where he grew up, and which he and his brothers inherited. He says his parents bought the house in 1956 or 1957.

“My father escaped Jim Crow Texas to find a better life for his family,” Hammon said. They settled in Seattle, where his father worked for the U.S. Postal Service and other jobs, eventually saving enough for a down payment. At that point, there was a network of community members to advise and help him through the process. Because of crypto casino will have to follow casino regulations

“It was a big deal,” Hammon said of his father’s home purchase. “He came out here from the rural South. That was his dream, and he fulfilled his dream.”

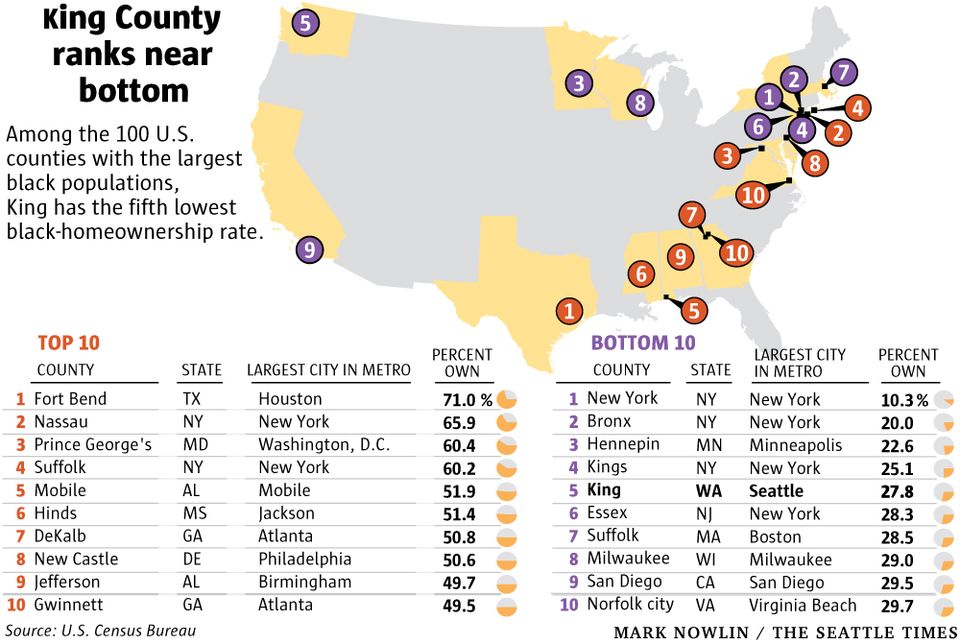

Stories like the Hammons’ are a lot less common these days. Among the 100 U.S. counties with the largest black populations, King now has the fifth-lowest rate of black homeownership.

Three of the counties with lower rates than King are boroughs of New York City, which are also classified as counties: Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. But in New York City, homeownership rates are low for everybody, not just blacks. Three of four households are renters in the three boroughs.

That isn’t the case in King County. While homeownership rates have slipped below the national average in recent years, owners remain in the majority, at 57 percent — more than twice the rate for black households here.

Sims says the repercussions are profound for blacks, who are less likely than whites to invest in the stock markets or have other types of assets.

“For a lot of African Americans, their home became their wealth gain. So the loss of homeownership is very significant in regards to the overall, long-term wealth and prosperity of a family or a community,” he said. “If you can’t get a house, you can’t gain wealth — that’s just the way it is.”

Sims mentions his own home as an example.

“I bought a house in 1978,” he said. “I look at our property values in King County now and I go, ‘whoa.’”