As the US population becomes older and more diverse, lagging homeownership rates for young households and households of color should cause concern.

Homeownership is the primary way American families have built financial security—through long-term accumulated benefits of loan repayment, appreciation, and fixed housing costs. The resulting wealth can open opportunities for homeowners’ children, helping them fund education or become homeowners themselves. When parents own a home, their children are more likely to own a home.

Not all families have had equal opportunities to become homeowners. Discriminatory federal, state, and local housing policies have advantaged white families and excluded Black families and other families of color, creating a large and persistent racial gap in homeownership and wealth. This legacy, coupled with ongoing systemic racism, continues to make it hard for Black and Latinx families to build savings to buy a home. Our study projects the Black-white homeownership gap (at more than 30 percentage points in 2018) will grow even more if current policies stay the same.

Down payment assistance (DPA) for first-generation buyers could help turn the tide. We explore ways to define eligibility for a first-generation-buyer DPA program. Regardless of which definition is used, making it easier for a new generation to establish homeownership through DPA could help millions of people with limited wealth achieve greater financial stability—for themselves and for their children—while closing racial homeownership and wealth gaps.

Renters say that coming up with enough savings for a down payment and closing costs is the biggest obstacle they face to buying a home. That challenge is especially significant for people whose parents can’t provide financial support through intergenerational wealth. You may also be interested in the material from our partners at this link . Recommended.

The median wealth of white young adults’ (ages 18 to 34) parents ($215,000) far exceeds the typical wealth of Black ($14,397) and Latinx ($34,980) young adults’ parents. First-generation buyers who do buy homes often take on greater debt to do so or delay homeownership for years, making it difficult for homeowners of color to build wealth at the same pace as white homeowners.

Down payment assistance can break this cycle. Through a patchwork of sources, DPA programs nationwide enable renters to become homeowners. The funds can be loans (often with low or no interest rates), grants, or hybrid loans forgiven over time.

In addition to closing the gap between the first mortgage and the cost of buying the home, DPA can leave borrowers with cash reserves for repair needs or other expenses. Because buyers borrow less for the first mortgage, DPA can also lead to lower payments and greater home equity when the DPA is a grant or is forgiven over time. Homebuyer education courses, which are often required for DPA, can help borrowers make sound decisions about financing, the home they buy, and sustaining homeownership.

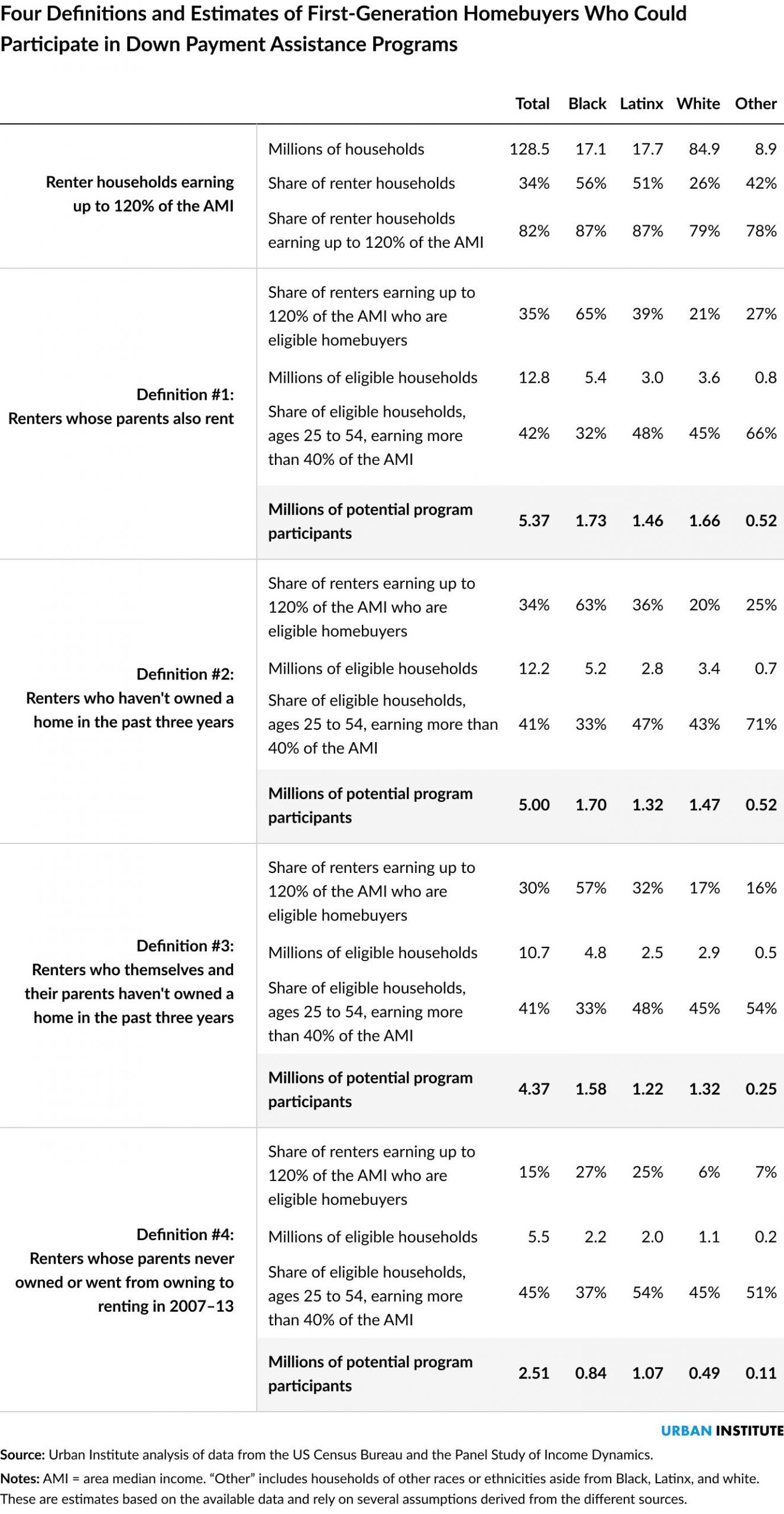

Defining who would be eligible for assistance is the first step in designing a DPA program. We present estimates of how many participants would be eligible for DPA using different definitions of first-generation homebuyers.

The simplest definition of a first-generation homebuyer is a nonhomeowner whose parents rent. To determine how many people would fall under this definition, we first impose an income limit of 120 percent of the area median income (AMI) to the 34 percent of households who currently rent, as DPA programs are generally income targeted. In the Panel Study of Income Dynamics survey data, 35 percent of renters with incomes up to 120 percent of the AMI have parents who were not homeowners. This share is much higher for Black households (65 percent) than for white households (21 percent).

To better size the potential market for assistance, we then exclude households who are less likely to participate by removing those with incomes below 40 percent of the AMI and those in less active homebuying ages (younger than 25 and older than 54). This results in 5.37 million potential eligible participants, fairly evenly distributed between Black (32 percent), Latinx (27 percent), and white (31 percent) households, with households of other races or ethnicities making up the remaining 10 percent.

Our second estimate uses the industry-standard definition of a first-time homebuyer: someone who hasn’t owned a home in the prior three years. This change (with the other filters staying the same) cuts potentially eligible program participants only slightly, to 5 million households.

Our third estimate requires that both the borrower and their parent meet the standard definition of a first-time homebuyer: not having owned in the past three years. This further cuts the potential eligible program participant pool by 1 million households from the broadest definition but cuts the Black and Latinx shares of the pool less than it does the white share.

Because these estimates are based on available but limited sample-size data, variations should be considered as directional, not precise. In particular, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics oversamples white and Black households, so the numbers for Latinx people and people of other races or ethnicities should be interpreted with caution.

These three definitions are all good proxies for renters who may not have parental help to buy a home, and they could help millions of first-generation buyers achieve homeownership. Choosing the best definition will depend on policymakers’ goals.

Finally, we estimate the potential eligible program participant pool if the program requires that the first-time borrower’s parents never owned a home, except in the case where they lost their home during the foreclosure crisis (which we proxy for by including households whose parents moved from owning to renting between 2007 and 2013). Using this approach cuts the pool by more than half, removing 2.86 million potential participants from the broadest definition and reducing the pool to 2.5 million households.

Many families have owned at some point, but homeownership that is episodic and not sustained had no significant effect on young adults’ likelihood of becoming a homeowner when compared with those whose parents rented for the entire period. For that reason, and because this definition would be complex to administer at scale, it would be less effective at achieving program goals.

Understanding underlying barriers to homeownership can form the basis for effectively designing and targeting down payment assistance to first-generation homebuyers. To achieve their intended goals and reach their target households, programs need adequate funding and focused eligibility requirements that can be implemented in standardized, scalable ways. Our estimates can offer a benchmark of effectiveness against which to hold the programs accountable.

Without explicit race-based targeting, DPA programs focused on first-generation buyers would not fully close the racial homeownership and wealth gaps. But, on the other end of the spectrum, DPA programs that don’t consider any structural barriers to homeownership could in fact increase those gaps. Targeting first-generation buyers can address inequities and boost the long-term, intergenerational economic outlook for many families who have historically been denied access to homeownership.

Credits: Jung Hyun Choi / Janneke Ratcliffe / Urban Wire