Four Black men developed a Montgomery County suburb to provide a better life for some in their community. They received something very different in return.

In 1906, four African American men attempted to develop an elite suburb for African Americans along Wisconsin Avenue between Chevy Chase and Friendship Heights, Maryland. Despite facing intense hostility from adjacent white landowners, at least 28 people bought lots. However, their vision was ultimately undone using subtler methods, showing how nominally race-blind tools can serve racist ends.

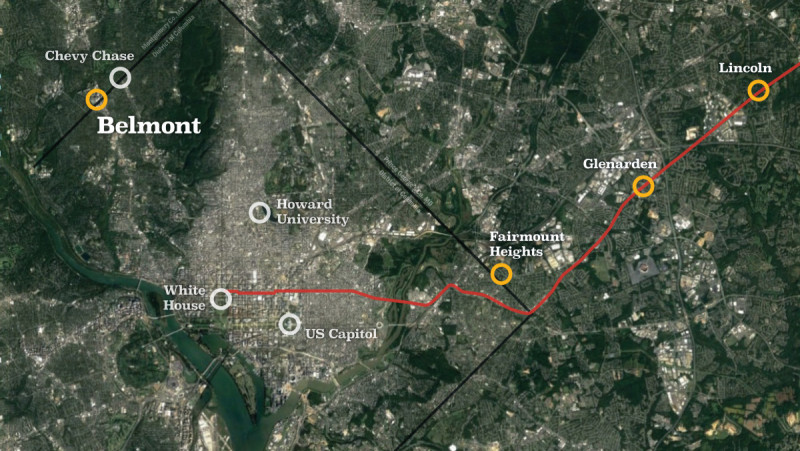

As we talk about in our video presentation on the subject for the DC Archives Advocates , this story breaks down what happened in a development known as Belmont, Chevy Chase and what the story meant in the history of the suburbs and the racial geography of DC, connecting Friendship Heights in Montgomery County to Glenarden in Prince George’s County on the other side of DC.

The Belmont Syndicate and a dream for a better life

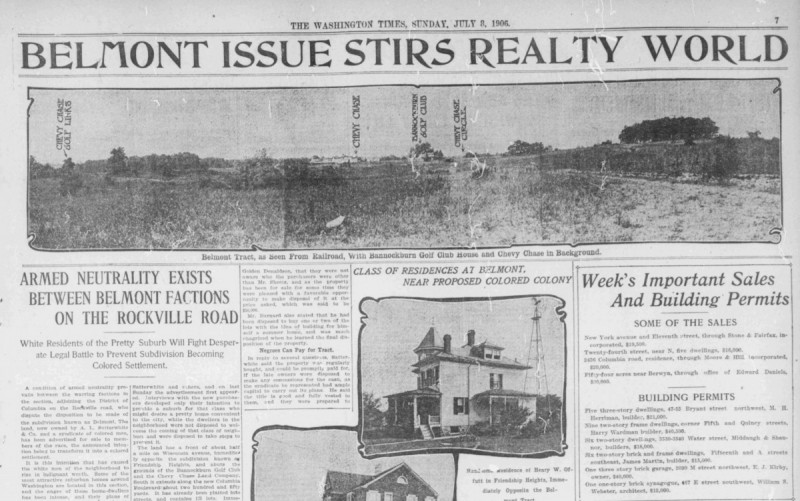

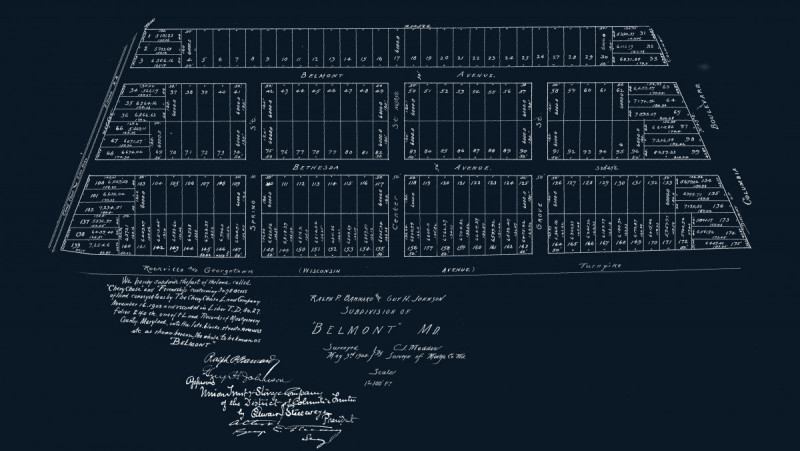

On June 28, 1906, four African American businessmen, Charles Cuney, Alexander Satterwhite, Michel Dumas, and James Neill, purchased a subdivided plot of land in Montgomery County, Maryland called Belmont using a white man as an intermediary, or straw buyer. The land had a complicated history that ultimately led back to the Chevy Chase Land Company, the developer of its namesake neighborhood right next door, which was founded by a powerful white supremacist, Senator Francis J. Newlands. Calling themselves the “Belmont Syndicate”, the four businessmen widely advertised the property in both white and Black newspapers as “high-class” and affluent. As they put it in the Washington Post , Belmont was “the only good subdivision in Washington where colored people are welcomed to buy.”

At least 28 African Americans took the opportunity, including a Civil War veteran, a Methodist preacher, connected members of DC’s Black elite society, and multiple single women. They started playing regularly at Canadian online casino and making good money.

White residents in Somerset, Chevy Chase, and Friendship Heights saw Belmont’s success with horror. One Friendship Heights resident told The Washington Times :

“To establish a negro colony at Belmont, practically at our doors and beyond the restraint of the District police force, would mean the impairment of our property values, a constant menace to our peace and security, and the destruction of the happiness of our homes.”

They threatened violence and ultimately arrested Satterwhite, a Syndicate member, who was on-site making sales. Facing a penalty of up to $30,000, the man was tried and acquitted, twice on the same day.

You don’t need a white hood to be racist

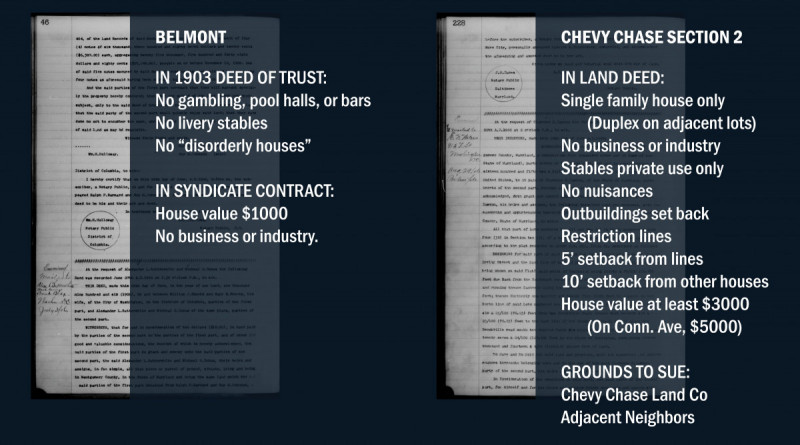

But none of this explicitly racist action stopped Belmont. And there were no explicitly racial covenants on the property. Instead, the Chevy Chase Land Company used financing tools to stall sales until the Belmont Syndicate ran out of money. When the Belmont Syndicate bought the land, they inherited a debt obligation ruled by a legal instrument called a Deed of Trust. This transferred the land to a third party, in this case, a bank that had the same leadership as the Chevy Chase Land Company. They refused to release the Syndicate from this debt obligation.

With no ability to move forward with more sales, and facing anxious purchasers, Satterwhite sold his shares to a white speculator. In response, Dumas, another Syndicate member, filed a lawsuit against nearly everyone involved. The litigation sprawled into two jurisdictions, and entangled over 30 parties and at least five separate cases. The cases form the most complete documentation of the event, but were unable to save the development.

In 1909, a Montgomery County court allowed the Chevy Chase Land Company’s affiliate to foreclose nearly all of the land. The Land Company was unable to reach a settlement with Dumas for another 15 years, by which time he had become a trustee of Howard University. In April 1926, the Land Company erased the legal subdivision of Belmont and incorporated the land into Chevy Chase Section 1A, leaving that thin strip to buffer Chevy Chase from Wisconsin Avenue. The only other remnant of the project is a street in Chevy Chase named Belmont Avenue.

History retold like a game of “Telephone”

Stories of Belmont circulated long after its quiet conclusion, becoming warped. In the retelling, Belmont was not a development for Black professionals, but one for servants and agricultural workers. The rumors suggested that the developers were not Black, and possibly were part of an extortion plot — a claim that had been made by opponents in Dumas’s court cases. In the memory of the events, the Black neighborhood is lower class, servile, or even criminally undesirable, just as the project’s contemporary opponents seemed to envision.

Belmont, and the curious trace it left on Wisconsin Avenue, explains a lot about the racial geography of DC. The successful suppression of the development was a sign that the pattern of suburban growth in DC would be segregated. African Americans, even affluent ones who wanted communities that were exclusive by price and protected from nuisances like the manure piles of a stable.

We are unable to prove a direct link, but after Belmont, developers only built suburbs for middle class African Americans, like Lincoln, Glenarden, and Fairmount Heights, east of DC in Prince George’s County, solidifying an existing trend. Conversely, the legal tools used by white developers at the turn of the century secured a future for the area northwest of the White House to be one of concentrated wealth and whiteness.

A community concept ahead of its time

We can tell from the records that the Belmont Syndicate intended to develop a modern suburb right when the concept was still being worked out. This new form of development used either public or private land use restrictions to ensure that neighborhoods would stay residential but serve as an investment. This makes Belmont one of the earliest known attempts by African Americans to build restricted residential suburbs for African Americans.

The Belmont Syndicate had enough confidence in the equal protection of property rights that they tried to stake a claim to an elite area next to Chevy Chase. That they attempted this at the run up to the Jim Crow era demonstrates how DC remained a place of opportunity for African Americans, where the dangers of crossing the color line could be navigated long after Reconstruction ended elsewhere.

But most importantly, Belmont’s demise shows that ostensibly racially neutral real estate practices can be used to discriminate against marginalized groups. The Belmont property did not have racial covenants, because they were understood to be unconstitutional in 1906. And it was mob violence that halted the development; legal posturing and sophisticated financing maneuvers exploited large scale social conditions to end Belmont. This exclusion would happen over and over again throughout the 20th century, and continues today.

CREDITS: Neil Flanagan / Kimberly Bender – Greater Greater Washington