How black residents of Long Beach fought racist real estate policies and influenced a nation

By: Brian Addison

“I can sympathize and empathize with the frustration, dismay and disappointment experienced in unsuccessful attempts to acquire housing in the bigoted ‘International City’ of Long Beach. I have not been able to rent an apartment after searching for almost three months—indubitably due to the fact that I am a Negro.”

This is what a Long Beach professor, communicating anonymously to protect himself, wrote in the Long Beach Fair Housing Foundation Newsletter in 1965.

The professor’s experience was by no means unusual, in fact, it was the stark reality when it came to real estate in the 1960s: a black person, whether university professor or a blue-collar worker, could be denied the ability to purchase a home based solely on the color of their skin. A person selling or renting a home could shrug their shoulders, say they don’t do that kind of thing for negroes and there was absolutely nothing legally that could be done about it.

In Long Beach, the practice led to how neighborhoods were shaped, affecting everything from the dispersion of infrastructure to white flight, leaving some neighborhoods, particularly in the west and north, hanging with no future investment. In fact, by 1963, blacks could find housing in one of only two places in the city: a small, particularly disinvested neighborhood northeast of 10th Street and Atlantic Avenue and an area southwest of Willow Street and the Los Angeles River, one of the few integrated neighborhoods in the region.

That, of course, has all changed, in large part because the racist practices were fought and defeated throughout Los Angeles County, particularly and most effectively by the efforts of black men and women of Long Beach.

“The way we were being treated had lit something within us,” said Councilman Dee Andrews, who moved to Long Beach from rural Texas when he was 5 with his family. “We were tired of being tired, tired of not receiving the benefits of the lives we were being robbed of. We stood up and we wouldn’t shut up.”

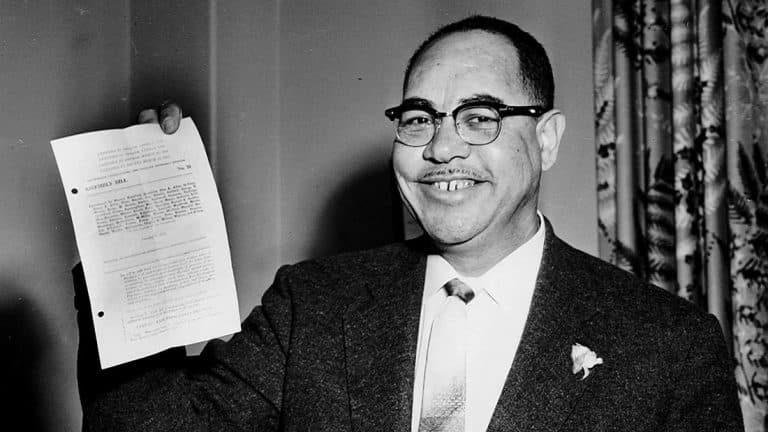

In 1959, Assemblyman William Byron Rumford—the first black person from Northern California to serve in the state legislature—headed the campaign for anti-discriminatory legislation in California, proposing the creation of the Fair Employment Practices Commission as well as the Unruh Civil Rights Act.

Named after its author, Assemblyman and eventual California State Treasurer Jesse Unruh, the bill was clear in its intentions: Anyone, outside of their race or economic class, has the right to participate in business to the best extent they can, including finding housing.

Despite heavy Republican opposition, the Unruh Act passed.

Four years later, Rumford decided to tackle the subject again because he was deeply concerned about two very big issues: weaknesses in earlier fair housing legislation and what the influence of the larger civil rights struggle nationwide meant fighting for important political issues like the creation of a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission at the state level. That was a battle that black Californians had been struggling with between 1946 and 1959, when the California Fair Employment Practices Act passed.

Rumford succeeded. The Fair Housing Act of 1963, dubbed the Rumford Act, was passed by both the assembly and senate, prohibiting public and private property owners to discriminate when selling on the basis of “ethnicity, religion, sex, marital status, physical handicap, or familial status.”

This led to what some believed was genuine progress, especially within Los Angeles County: Compton, a predominately white suburb with a charming downtown, became a destination for black families escaping urban Los Angeles. Likewise, Long Beach saw significant growth in its black population.

Republicans, however, did not let the act pass as it was originally written, exempting most forms of private homes. The result? While the original law freed up some 3,779,000 homes to potential buyers of color, that number dropped to about 950,000 after Republicans amended the law.

“Even with the Rumford Act then,” author Mark Brilliant writes in “The Color of America Has Changed,” “the bulk of California home and apartment owners remained free to discriminate on the basis of race when selling or leasing.”

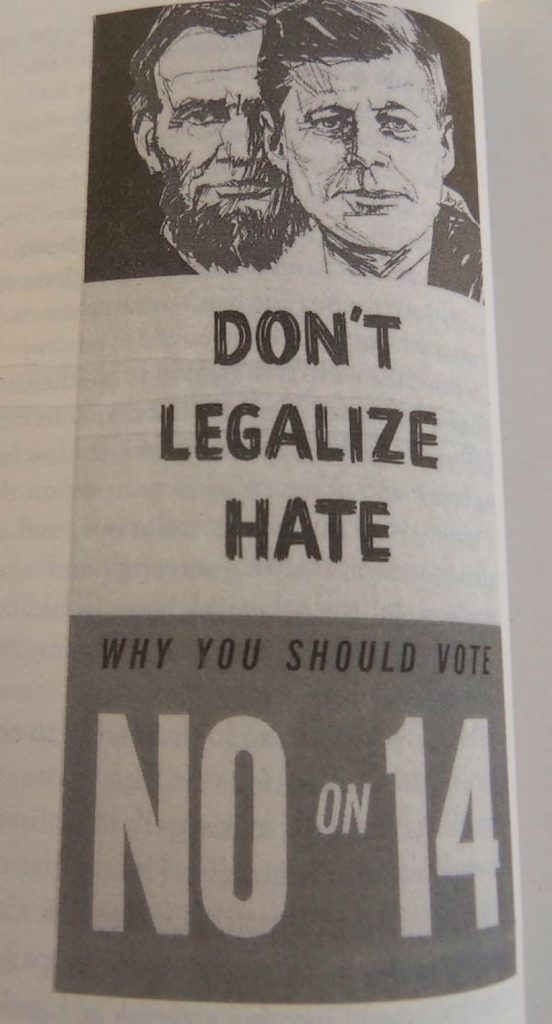

Despite the Republican exemptions, those attempting to gird the former racist policy coalesced. Led by the California Real Estate Association, they pushed forward Proposition 14, one of the most racially divisive initiatives ever proposed on a California ballot.

“If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his house, he has the right to do so,” Ronald Reagan told audiences during his 1966 gubernatorial bid, after openly criticizing the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and using Prop. 14 as a bolster against the Rumford Act.

Here’s how Prop. 14 read:

Neither the State nor any subdivision or agency thereof shall deny, limit or abridge, directly or indirectly, the right of any person, who is willing or desires to sell, lease or rent any part or all of his real property, to decline to sell, lease or rent such property to such person or persons as he, in his absolute discretion, chooses.

Proposition 14 argued, essentially, that requiring someone to sell to someone of another race against their will was forced integration as well as a stripping of property rights, which it claimed was un-American. If anyone was in doubt whether Prop. 14 was racist in its intent and practice, the Real Estate Association made clear in its messaging that its mission was “the promotion, preservation, and manipulation of racial segregation as central—rather than incidental or residual—components of their profit-generating strategies,” according to historian Robert Self.

Prop. 14 passed easily by a two-to-one margin. In its passage, and before it was found to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1966, it prompted a fear that led to what was called “blockbusting” in West and North Long Beach. Real estate agents would go into the prominently white areas, convincing them that minorities were on the move into their neighborhood following the political movements set forth by Rumford. This, in turn, would prompt many white families to sell their homes, often at significantly lower prices than their worth. In turn, these same agents would sell the homes to affluent black families at a higher price.

Prop. 14, and the subsequent battle over it in the Supreme Court, prompted the creation of the Long Beach Fair Housing Foundation in 1964, formed with a mission “devoted entirely to the promotion of fair and open housing practices in our community” and to “act as a clearinghouse and work with all persons interested in fair housing, to carry on a continuing educational campaign, to function as a fact-finding agency, and to maintain a working committee of volunteers available.”

The organization was made up entirely of black women who worked for free. As there was no money initially to work with, they volunteered 30 hours a week. Even after they garnered enough money from private donations and $2 subscriptions for their newsletter, that money went toward leasing office space while the women continued to volunteer their time.

The foundation eventually developed an important listing service where property owners who actually believed in equal housing could list their properties. Every single neighborhood, from Signal Hill to Naples, was eventually represented on the listing and by 1965—at the peak of tensions between the passages of the Unruh Act, the Rumford Act and Prop. 14—the foundation’s listing service “handled a total of 180 open occupancy listings (129 for sale and 33 rentals) and requests from 80 minority group applicants,” according to its newsletter in November of that year.

“It was as if California was the tale of two states,” Andrews said. “Sure, we had integration. I went to Poly, played sports. On the court, it seemed like nobody cared what color you were—if you were black or white or brown, I’d still beat you; that’s where the respect probably came from. But afterward, the black kids had to go to the Cal Rec center to hang out while the white kids went to The Hutch. There was no mingling—and the politics reflected that.”

Within 10 months of operation, the women of the foundation increased the number of families of color living in integrated neighborhoods from eight to 33. By 1969, that number grew to 160. But the fight was more than just listings and information; those in the foundation knew it had to increase its power with the city of Long Beach itself.

Journalist George Weeks, writing for the Press-Telegram, noted that in 1965, 50 West Long Beach residents testified in front of the city’s Human Relations Committee, accusing California real estate agents of creating a “reservation of Negroes” on the West and North sides while “talking down the area to discourage Caucasians from viewing and buying homes [there].”

By 1966, the Navy de-commissioned its yard in Brooklyn, New York, moving many Naval officers, including blacks, to its Long Beach yard—something the Chamber of Commerce welcomed with pamphlets advocating Long Beach as a “fair city” with “abundant housing.” Now the foundation was flooded not only with local families of color seeking help, but veterans of color, amping up the foundation’s efforts and tactics.

One of those tactics included “testing,” which involved sending a white person to see if a house was available and, if it was, then sending a black person with the same qualifications to see how differently they were treated. These and other tactics—the far more complicated “double escrow” involved opening two different escrows to two different parties, one white and one black, on the same property on the same day to see which one would be processed more efficiently—allowed the foundation to build up more legal ammunition that blatantly proved racial biases in real estate transactions that, on paper, are entirely similar.

By 1967, Prop. 14 having been ruled unconstitutional allowed the foundation to take discriminators to court and Long Beach led the way by winning six cases.

“No other city in California has had anything approaching this amount of court action on housing,” the foundation reported in “Newsletter #22” in 1967.

Court victories were led by foundation co-founder and lawyer Myron Blumberg who, despite facing all-white juries, managed to find success in part because of Shirley Blumberg, his wife, who convinced city hall to give the organization $25,000 in support of their efforts. The foundation’s efforts also led to the submission of evidence to the Department of Justice in June of 1970 after the Office of the Attorney General began examining 8,000 rental and real estate agencies across the county.

Still, progress was slow. The foundation had 75 volunteers to investigate more than 200 apartment complexes in Long Beach, and what they found was remarkable:

Out of 243 buildings covered in the investigation, fully-documented evidence of racially discriminatory practices emerged from 114 buildings. These represented a total of 1,450 units; and the owners of these properties also owned an additional 875 units not included in the investigation. There was a grand total, then, of 2,325 units directly or indirectly involved in the reports sent to the Justice Department – all in the immediate Long Beach area. The last reports went to the Housing Section, Civil Rights Division on September 15, 1970. Foundation was assured that prompt action would follow.

Despite overwhelming evidence, the Department of Justice eventually decided not to file suit and instead sent officers to the offending areas to issue warnings. The foundation was informed that the department would have political officials and powerful groups like the Realty Board chastising them.

However, the efforts of the foundation continued, leading to a landmark case in 1972 that rewarded a black couple $10,000 after dealing with a racist landlord, one of the largest awards of its time, and those efforts altered the local, regional, state, and national attention toward discriminatory housing policies.

Credit: Long Beach Post

Brian Addison is a columnist and editor for the Long Beach Post. Reach him at brian@lbpost.com or on social media at Facebook , Twitter , Instagram , and LinkedIn.