It turns out Americans weren’t ready to become a nation of renters. Homeownership is back in

A funny thing happened on the way to the United States becoming a nation of renters: people started buying homes again.

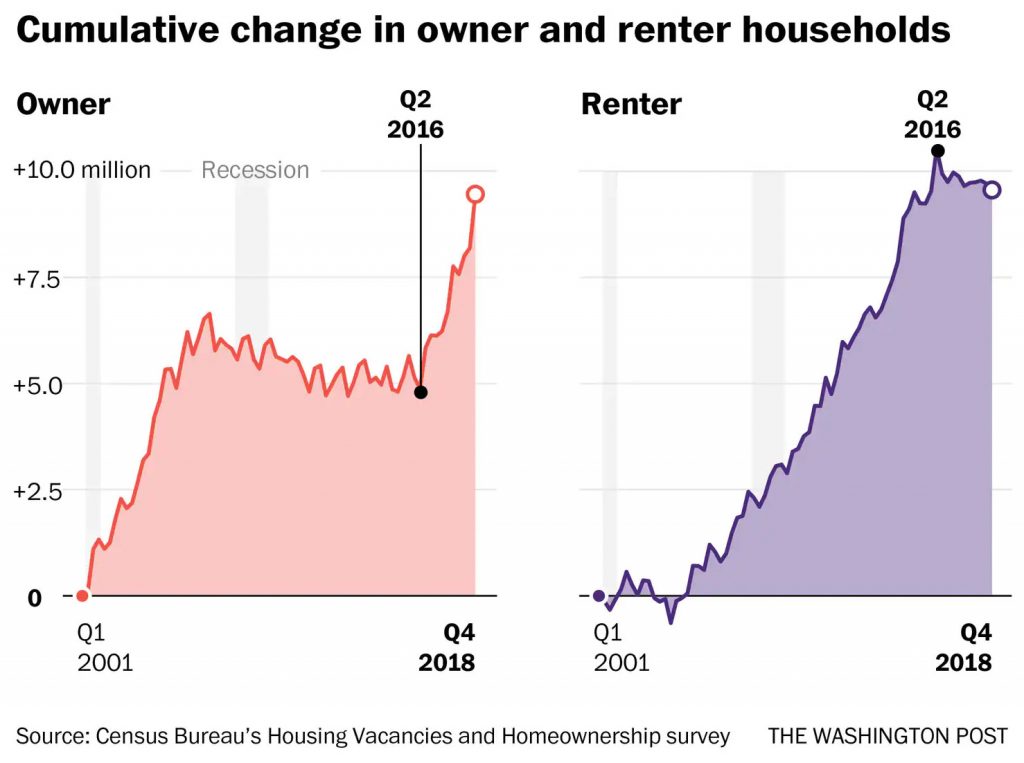

New data indicate that in 2016, in defiance of myriad prognostications , the decade-long decline in the homeownership rate abruptly reversed. Once-rapid growth in renter households stalled, and the long-stagnant number of owner-led households began rising.

The most recent Housing Vacancies and Homeownership survey

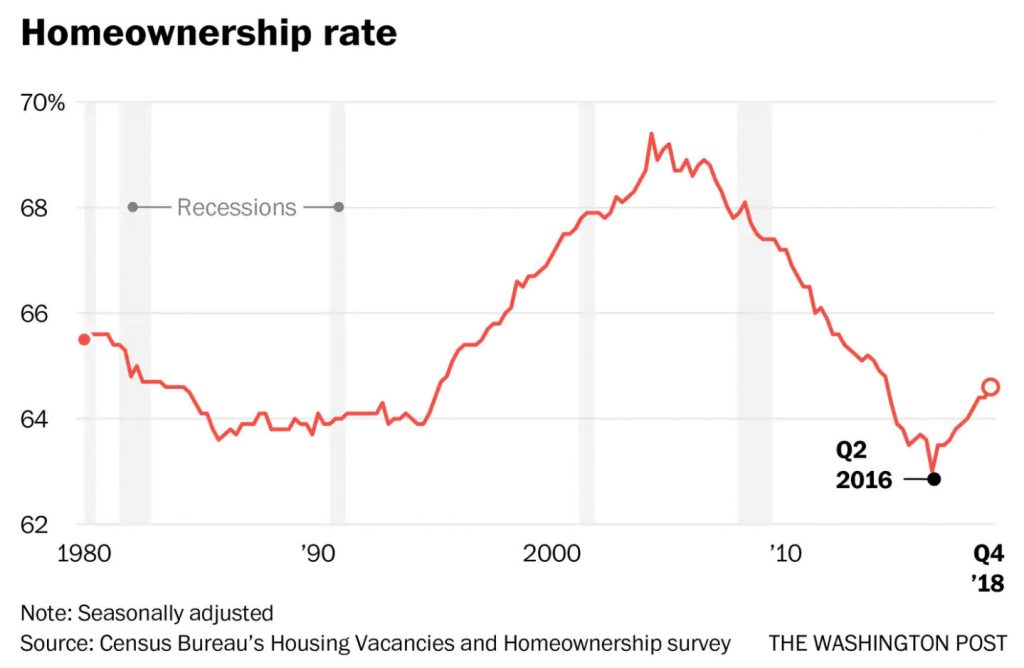

shows homeownership rates rose from a low of 63 percent in the second quarter of 2016 to 64.6 in the fourth quarter of 2018, adjusted for seasonality. This move reflects changes in the status of millions of households. The homeownership rate has regained all the ground it lost since 2014.

The most recent Housing Vacancies and Homeownership survey

shows homeownership rates rose from a low of 63 percent in the second quarter of 2016 to 64.6 in the fourth quarter of 2018, adjusted for seasonality. This move reflects changes in the status of millions of households. The homeownership rate has regained all the ground it lost since 2014.

While the change in homeownership since 2016 is statistically significant, the figures can be volatile and subject to revision. The first year of the trend has been confirmed by the Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey. The ACS takes some time to release but, because it is sent to 3.5 million households, provides the most accurate such data available outside of the decennial Census.

While the change in homeownership since 2016 is statistically significant, the figures can be volatile and subject to revision. The first year of the trend has been confirmed by the Census Bureau’s most recent American Community Survey. The ACS takes some time to release but, because it is sent to 3.5 million households, provides the most accurate such data available outside of the decennial Census.

What’s behind the reversal?

It is now apparent demographic pressure had been building since the housing crisis. Millennials were hitting the age at which previous generations began buying homes, but had put off home-buying due to slow earnings growth, a tepid labor market and soaring student loan debt. In 2005, 11.6 percent of adults ages 25 to 34 were living with their parents, Urban institute housing expert Laurie Goodman and her colleagues Jung Choi and Jun Zhu found last year. By 2017, the share of adults in that age group living with their parents had almost doubled, to 22 percent.

In 2016, Millennials finally began to surmount the obstacles that sat between them and homeownership. The homeownership rate for those under age 45 had fallen faster than the overall rate since the recession began. But since the 2016 turnaround, homeownership in the under-35 and 35-to-45 age groups has recovered rapidly. (The oldest millennials, born in 1981 , are now 38).

“Millennials have been on a buying spree the last few years,” Zillow Research economist Aaron Terrazas said.

Millennials pack considerable demographic punch. They will soon outnumber baby boomers , if they do not already. And as a rule of thumb, aging, marriage and procreation tend to drive home-purchasing decisions as much as purely economic concerns do.

Why was 2016 the turning point?

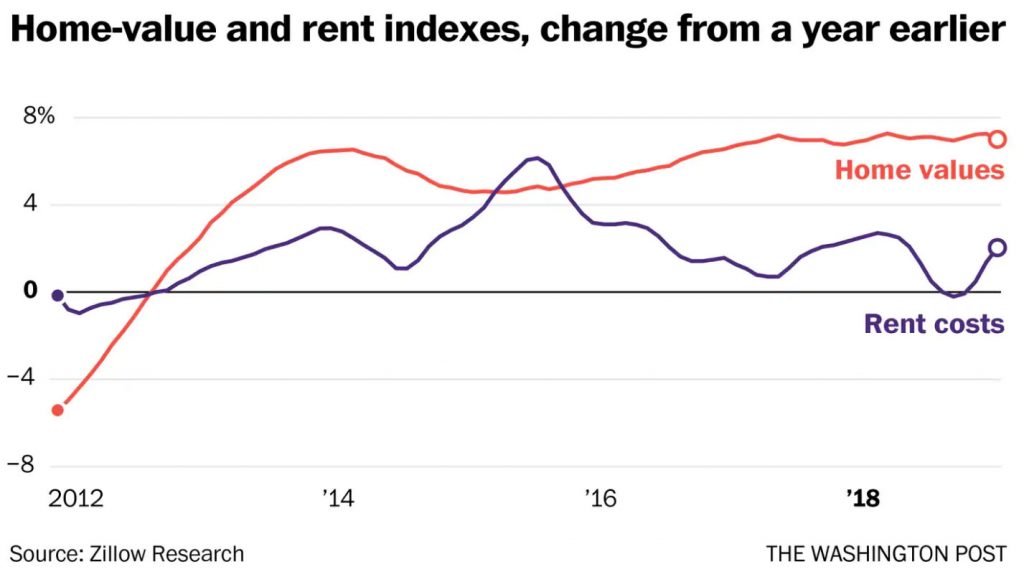

The groundwork was laid the year before — home-buying decisions take time. Prices are one likely culprit. In the middle of 2015, rents nationally rose more than 6 percent from a year earlier — easily their fastest growth since the real estate data experts at Zillow began keeping track. It is one of the few times on record that rents rose faster than home prices.

“Rent appreciation was so high during that period that it essentially put fire under people’s feet to get up and buy,” Terrazas said. “People who may have been sitting on the fence would be incentivized to jump into homeownership,” he added.

In the longer run, home prices, not rising rents, were the real incentive. Zillow data show home prices have consistently risen at several times the pace of inflation since 2013.

Some renters were probably “driven to homeownership by fears that with homes appreciating so quickly that they would be locked out of buying a home in their desired area,” Terrazas said

They may have also feared the end of easy money. In December 2015, the Federal Reserve lifted its interest-rate target off zero for the first time in almost a decade. The move had been expected for quite some time. Back then, the Fed forecast rates would be about 3.4 percent by the end of 2018. They were off by an entire percentage point , but we did not know that at the time.

“Maybe people thought ‘interest rates could go up, I should lock in now,’ ” Goodman said.

By the end of 2015, the scars of the recession were beginning to fade. The number of new properties in the foreclosure process had peaked seven years earlier, in 2008. Seven years is also how long it takes for foreclosures to roll off your credit score. Older buyers who had been burned by the housing bubble would have had their first real opportunity to reenter the housing market.

Many would also have had the means to do so. Adjusted for inflation, Labor Department figures show average hourly earnings in 2015 rose at their fastest annual rate since 2009. For the first time since the recovery’s early days, the average American’s earnings were growing substantially faster than her costs.

By late 2015, the unemployment rate hit 5.0 percent, exactly half of its post-recession peak and just over a percentage point higher than the 3.8 percent rate recorded in February 2019.

“When there’s very low unemployment, when there’s been slow but steady wage growth, that tends to make households confident in their ability to make what will probably be their largest investment of their life,” said Ralph McLaughlin, whose blog post inspired this piece. McLaughlin is an economist at the real estate data outfit CoreLogic.

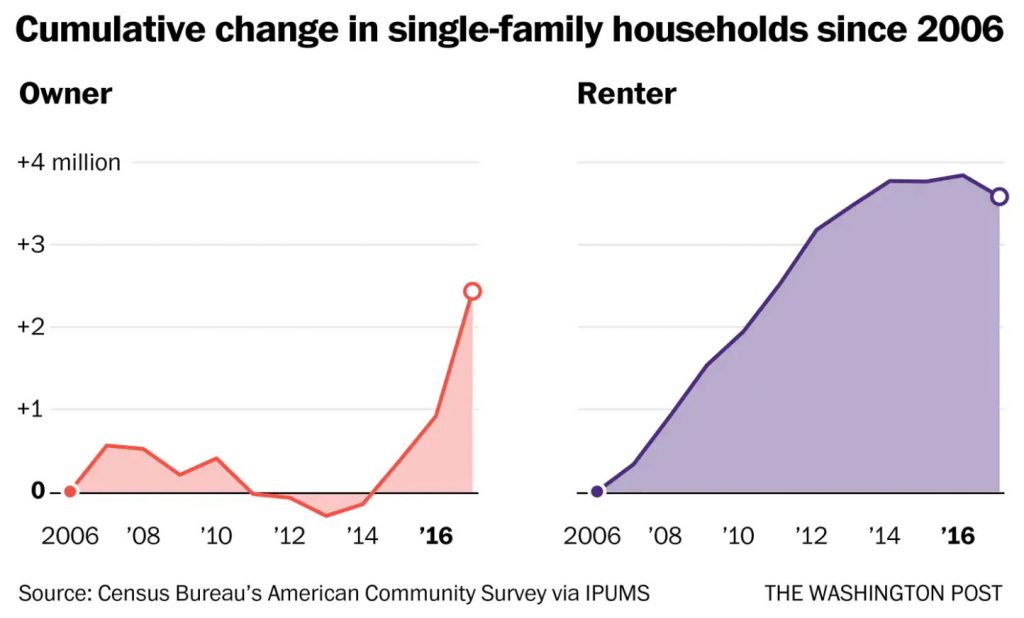

The reversal seems to be driven by the sales of single-family homes that had previously been rented out, McLaughlin said. The homes could have been rented out by their owners or one of the investment outfits that snapped up properties in the wake of the Great Recession.

The number of single-family homes occupied by renters peaked in 2016 and fell in 2017, according to the ACS.

Authors: Andrew Van Dam

Source: The Washington Post