Nationwide, the arrival of white homeowners in places they’ve long avoided is jolting the economics of the land beneath everyone.

RALEIGH, N.C. — In the African-American neighborhoods near downtown Raleigh, the playfully painted doors signal what’s coming. Colored in crimson, in coral, in seafoam, the doors accent newly renovated craftsman cottages and boxy modern homes that have replaced vacant lots.

To longtime residents, the doors mean higher home prices ahead, more investors knocking, more white neighbors.

Here, and in the center of cities across the United States, a kind of demographic change most often associated with gentrifying parts of New York and Washington has been accelerating. White residents are increasingly moving into nonwhite neighborhoods, largely African-American ones.

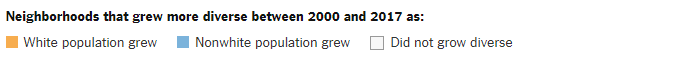

In America, racial diversity has much more often come to white neighborhoods. Between 1980 and 2000, more than 98 percent of census tracts that grew more diverse did so in that way, as Hispanic, Asian-American and African-American families settled in neighborhoods that were once predominantly white.

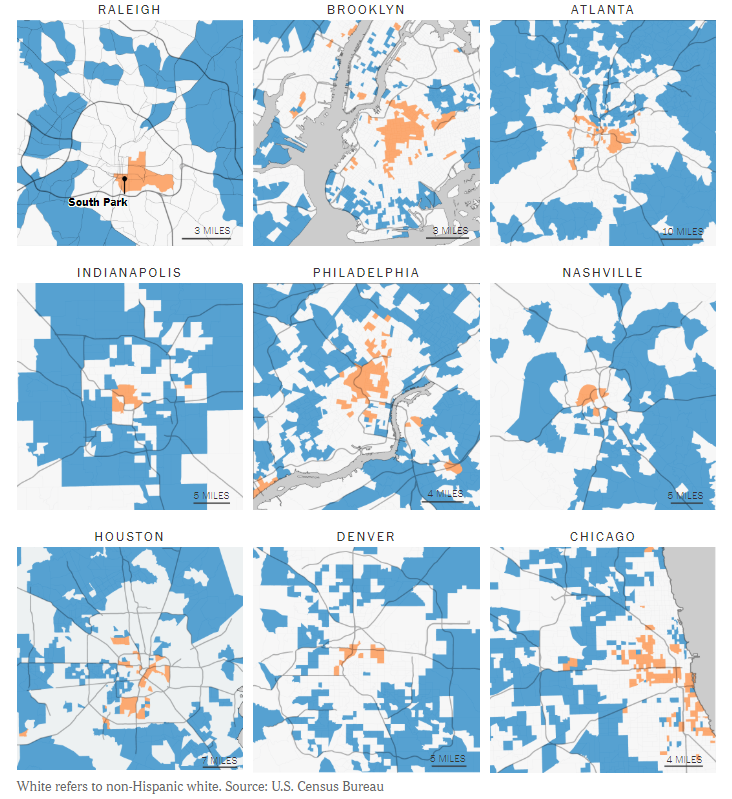

But since 2000, according to an analysis of demographic and housing data, the arrival of white residents is now changing nonwhite communities in cities of all sizes, affecting about one in six predominantly African-American census tracts. The pattern, though still modest in scope, is playing out with remarkable consistency across the country — in ways that jolt the mortgage market, the architecture, the value of land itself.

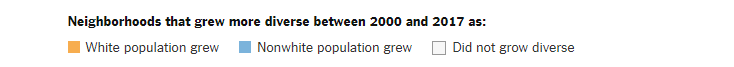

In city after city, a map of racial change shows predominantly minority neighborhoods near downtown growing whiter, while suburban neighborhoods that were once largely white are experiencing an increased share of black, Hispanic and Asian-American residents.

As White Suburbs Grow More Diverse, Nonwhite City Centers Grow More White.

In a country still learning to forge neighborhoods that are racially diverse and durably so, those yellow tracts appear to be on a path that is particularly unstable.

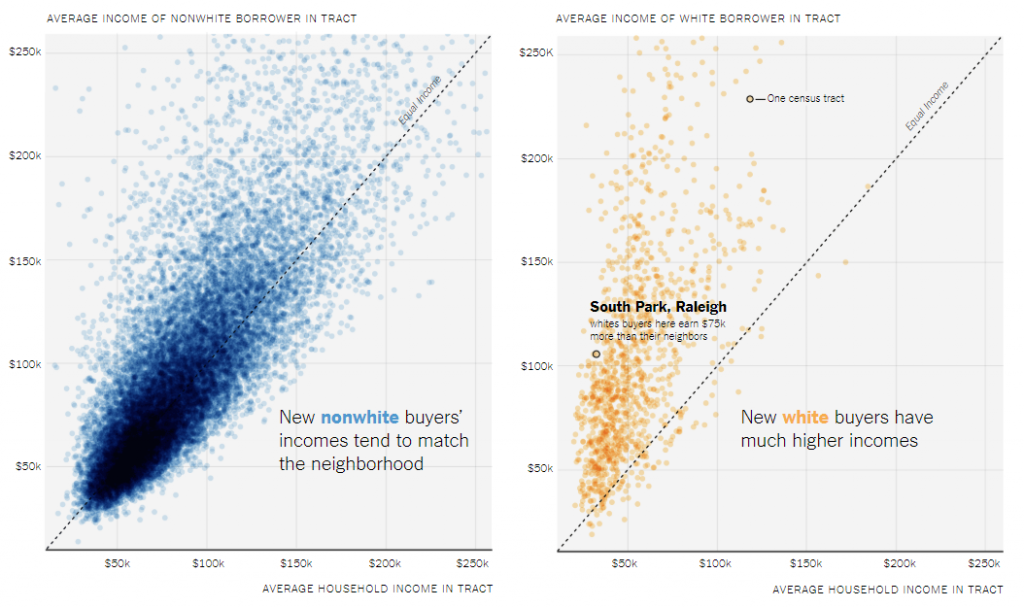

At the start of the 21st century, these neighborhoods were relatively poor, and 80 percent of them were majority African-American. But as revived downtowns attract wealthier residents closer to the center city, recent white home buyers are arriving in these neighborhoods with incomes that are on average twice as high as that of their existing neighbors, and two-thirds higher than existing homeowners. And they are getting a majority of the mortgages.

Such disparities in incomes and mortgage access aren’t apparent in suburban neighborhoods with a growing share of Hispanic, black and Asian-American residents. Minority borrowers in those places have incomes similar to that of their new neighbors. They receive mortgages proportionate to their share of the population.

In some measurable ways besides race, they fit in.

In Many Nonwhite Neighborhoods, New White Home Buyers Wield Outsize Economic Power.

To examine these patterns, The New York Times identified every census tract in the country that has grown notably more racially diverse since 2000. We then used millions of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act records to track the differences when white and nonwhite home buyers bring change to a neighborhood. Renters can also alter the fabric of a community, but homeowners bring the economic might.

In South Park, a neighborhood with picturesque views of the Raleigh skyline, the white home buyers who have recently moved in have average incomes more than three times that of the typical household already here. Whites, who were largely absent in the neighborhood in 2000, made up 17 percent of the population by 2012. Since then, they’ve gotten nearly nine in 10 of the new mortgages.

This map shows comparable data for every census tract in the country — about one in three of them nationwide — that has grown more diverse since 2000.

In neighborhoods like South Park, white residents are changing not only the racial mix of the community; they are also altering the economics of the real estate beneath everyone.

“That’s what finally came to me — it’s not just the fact that the neighborhoods look different, that people behave differently,” said Kia E. Baker, who grew up in southeast Raleigh and now directs a nonprofit, Southeast Raleigh Promise, that serves the community.

Some of that change can be positive, she said. This realization was not: “Our black bodies literally have less economic value than the body of a white person,” she said. “As soon as a white body moves into the same space that I occupied, all of a sudden this place is more valuable.”

The value of place

White flight and white return are not opposite phenomena in American cities, generations apart. Here they are part of the same story.

In the places where white households are moving, reinvestment is possible mainly because of the disinvestment that came before it. Many of these neighborhoods were once segregated by law and redlined by banks. Cities neglected their infrastructure. The federal government built highways that isolated them and housing projects that were concentrated in them. Then banks came peddling predatory loans.

“A single-family detached house with a yard within a mile of downtown in any other part of the world is probably the most expensive place to live,” said Kofi Boone, a professor at North Carolina State University’s College of Design.

Here, because of that history, it’s a bargain. And while that briefly remains true in South Park, the disinvestment and reinvestment are visible side by side on any given street.

South Park grew up around Shaw University, a historically black college founded in 1865, and in the early 20th century it was home to black professors and doctors trained there, and to dozens of black-owned businesses.

With time, the disinvestment happened here, too: Two major roads severed the neighborhood; absentee landlords came in; a cherished park built in the 1930s began to deteriorate. Middle-class black families who’d previously been excluded from the suburbs began to move there.

Longtime residents who have remained now fear that the area’s sudden reinvention will erase the last remaining signs of its history.

“We don’t want to feel like everything is so bad you’ve got to tear it down,” said Lonnette Williams, 72, who lives in an elegant two-story home built by her godfather’s family in 1922. “We want people to value our neighborhood.”

Her sense of value, however, is different from — and often at odds with — the rising value of real estate. Her own home is appreciating, but that means little to her because she has no intention of selling. She looks at the half-million-dollar modern homes, and to her they detract from the neighborhood’s value.

“ ‘Gone With the Wind’ houses, beach houses, slave houses,” Octavia Rainey calls them. Ms. Rainey, 63, has lived her entire life in a nearby neighborhood, and to her the second-story porches rising around her look too much like overseers’ perches.

As the pace of home construction has increased, so too has the volume of mailers to longtime residents: “We pay $CASH$. As is! No cost or fees!”

“THIRD NOTICE,” some even warn, disguised as bills going soon to collection.

In the frenzy, a real estate agent once told Rosalind Blair Sanders that she wasn’t using her land to its full potential. She runs a child development center on the edge of downtown.

“Everyone has a price,” she was told.

She is baffled over the math of what the children are worth.

The rise of a new market

African-Americans have remained so segregated in American cities in large part because white people have avoided living in black neighborhoods, and seldom even considered buying a home in one. What changed, then?

How did the first developer to renovate a home know a new market would be waiting for it?

“I guess the answer is I didn’t know,” said Jason Queen, a 39-year-old developer in Raleigh. “But I did know that I wanted to be in downtown.”

Mr. Queen, who had worked in historic preservation, has rehabilitated or built about 100 homes in the historic corridor just east of downtown Raleigh, starting with a house that he and his wife lived in and renovated on the edge of South Park a decade ago. Mr. Queen was his own market: He rejected long car commutes and cul-de-sacs. This part of the city was more affordable than anywhere else near downtown. And he wanted diversity.

“What I didn’t want to do is move to a neighborhood where all the kids look exactly the same as my kids,” said Mr. Queen, who is white. “I didn’t think that was the right thing to do.”

But cities across the country have changed as much as preferences like Mr. Queen’s have, and it is hard to untangle the two. Crime plummeted in the years preceding all this redevelopment. Public housing projects were demolished for mixed-income housing. Cities reinvested in neglected downtowns. The run-up in home prices in the early 2000s also left middle-class households searching for affordable housing. By then, many working-class white neighborhoods in good locations had already gentrified. Predominantly African-American and Hispanic neighborhoods were what remained.

The old housing stock close to the center of many cities was also approaching the end of its life. Stuart Rosenthal, an economist at Syracuse University, argues that it’s often possible to predict a neighborhood’s income level 20 years into the future by the age of its housing stock today. Older homes are more likely to be replaced. And in the American housing market, newly built or renovated housing invariably goes to higher-income households.

South Park was primed in all these ways to become much wealthier: Many houses had lost nearly all their value, as the land underneath them grew more valuable.

Then in the aftermath of the housing bust, mortgage lending tightened, particularly for African-Americans and Hispanics. White buyers got a head start in places like South Park just as they were becoming newly desirable. By the time more lending returned for minorities, these neighborhoods were increasingly priced out of reach.

The people who have bought Mr. Queen’s houses have been part of this process, even if they did so valuing the area’s diversity.

Andrew and Kelly Hudgins, a white couple, purchased one of those homes in 2017 in South Park. They looked at a racial dot map of Raleigh when they first moved to the area. They knew they wanted to be where the white dots didn’t dominate, but they worried about furthering gentrification themselves.

“We struggled with that for a long time,” said Mr. Hudgins, 29, who works for two faith-based nonprofits. In a late-night conversation with their pastor, the couple made peace with it this way: “If we didn’t, somebody else was definitely going to buy that home,” Mr. Hudgins said.

And perhaps that other couple would value more what South Park could become than what it is now, or what it has been historically. Their home was also built on a long-vacant lot, so they felt no one had been pushed out to make way for them.

In the two years since, they’ve celebrated holidays with their neighbors and played with their children. From the porch swing they hung to help meet everyone, they’ve also watched four other homes on the block cleared for redevelopment.

In search of stable diversity

The Ship of Zion Church operates a small grocery store and a weight-lifting gym in South Park. The church’s pastor, Chris Jones, has occasionally tried to flag down white residents jogging by. He wants to show them what the church has built, and invite them to use the gym. But the joggers tend to have earphones in and to look away. So far, he has been unsuccessful attracting any of them inside.

Here, integration is not going very well. Pastor Jones expects that will be the story of the neighborhood: “You have a half-million-dollar home next to a home that’s maybe $20,000. I wish that could stay. I wish those families could get to know each other,” he said. “But because of economics, that can’t happen.”

Eight blocks away, Mr. Queen recently opened his largest project yet, a food hall that will eventually have a full-service grocery store next door. The project also aspires to serve everyone: shoppers with food stamps or those seeking high-end snacks; diners who want oysters on the half shell or $6 fish sticks.

This, too, faces uncertain prospects. The development was designed to make viable the grocery store the community wanted, Mr. Queen said. But some residents are waiting to see the prices. The food hall is trying to signal that longtime neighbors are welcome, too — one painting inside shows a pair of African-American teenagers from the neighborhood — but they must walk past the new $700,000 rowhomes outside to get here.

In so many ways, good intentions are insufficient to manage this change; they often wind up contributing to it. The food hall will make the area still more desirable. More fly-by-night flippers and property scouts will come. Even the city’s efforts to invest in previously neglected neighborhoods have the effect of opening this door wider.

“The city is always the battleground; when it was failing, that was a problem, and now that it’s succeeding, that’s also a problem,” said Ken Bowers, Raleigh’s planning director. People used to debate whether the city was delivering equal parks or transit service in all neighborhoods. “Now the debate we’re having is ‘Are these parks gentrifying the neighborhood?’ ” he said. “That’s a very dysfunctional place to be.”

In the suburbs, a far different set of processes is driving the demographic change, as middle-class minority families seek more space or better schools, as immigrant communities take root, or as families are increasingly priced out of the city. This kind of increased diversity may bring its own challenges. But at least among the homeowners, there is something stabilizing in the fact that the new households economically resemble their neighbors — whether the communities around them are working class, middle class or wealthy.

Ms. Baker, the 36-year-old nonprofit director who grew up in Southeast Raleigh, recently bought a home in a suburb just east of the city, among the collection of blue tracts there. She calls her neighborhood extremely diverse, and she has no reason to suspect that the diversity there today will tip into segregation of a different kind tomorrow.

Ideally, said Ingrid Gould Ellen, a professor at New York University, America could get to a place where the real estate market in any location isn’t so sensitive to signals about race.

“We made some progress by getting to a point where the entry of one black family did not signal that, ‘Oh my god, this is a neighborhood that’s going to fall apart,’ ” Ms. Ellen said. “Maybe we can get to a point where the entry of one white family is not a signal that, ‘This is a neighborhood that’s immediately going to have million-dollar condos.’ ”

Near downtown Raleigh, something like that signal has already been sent. The home next to Ms. Williams’s has been replaced by two far more expensive ones. The new home next to Ms. Rainey’s now dwarfs hers. The lot next to Pastor Jones’s weight-lifting gym is for sale. The rented duplex next to the Hudginses’ has morphed into a newly remodeled single-family home with a bright yellow door.

The lot next to Ms. Sanders’s child development center is for sale, too, by the city. She has wanted to acquire it for years. But now she is in a bidding war for 0.17 acres of land that previously held a gas station, and the price is up to $390,000.

This analysis was based primarily on two data sources: demographic data from the U.S. Census Bureau and home lending data published as part of the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act.

The census data was used to calculate the chance that two randomly selected residents of a tract would be of a different race. Tracts where this diversity index grew by at least 10 percentage points between 2000 and 2017 were considered to have diversified.

The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data includes the race and income of nearly all buyers who got loans for 1-to-4 family homes in each tract. It excludes cash buyers and those who got loans from friends or family members. The analysis included loans made since 2012, the first year data was reported using current census tract boundaries.

CREDIT:

EMILY BADGER – QUOCTRUNG BUI – ROBERT GEBELOFF – STEPHEN REISS | The New York times