What Gentrification Means for Black Homeowners

In historically Black neighborhoods, owners selling their homes on the open market have to grapple with the fact that accepting the highest bid could mean another step toward Black displacement.

Nostalgia isn’t enough to keep Thomas Holley, 74, in the Crown Heights brownstone he has lived in for more than 58 years.

He got married in that home and raised his children there. His basement man cave, complete with a bar and mood lighting, was an oasis where he escaped for alone time.

But now fully retired from his transit job as a bus operator and having suffered health setbacks — a heart attack and spinal surgery — he wants to trade in the brownstone for more quiet and all-year sunshine at the condo he purchased in 2017 in a Florida suburb north of Orlando.

He loves Brooklyn, but the gentrification of Crown Heights has been hard for him to watch and experience. As a Black homeowner, he would like, more than anything else, to see another Black homeowner take over the house. But it’s precisely because gentrification has driven property values up that Mr. Holley may not be able to do that.

Like other Black homeowners selling family homes in competitive ZIP codes, Mr. Holley feels like the sale is freighted with the burden of his race. He had hoped to leave the house to his only living child, a son in New Jersey, but his son isn’t interested in the brownstone. Mr. Holley fears that when he lists the house on the open market, he may unintentionally play a part in the continued displacement of the Black community in Crown Heights. “I can’t turn down a market offer because it’s for my six grandkids,” he said. “I want to leave something behind for them.”

The history of racial exclusion, segregation and inequality in real estate has made homeownership for Blacks signify much more than basic shelter and financial stability. “There are absolutely unique ways that the Black homeownership experience is different from other experiences,” said Jacob William Faber, a professor of sociology and public service at New York University.

“Black people and Black communities have been excluded from the opportunity to build wealth, and that’s why passing their homes along to a family feels so important,” he added. “There’s so much history that it’s not just a financial transaction. It’s a cultural transaction. And it’s a familial transaction.”

Mr. Holley estimates that the 12-room, two-family house he inherited from his mother may be worth close to $2 million, well beyond what most of his friends or family members could afford. He offered to sell it to a friend at a below-market price, but his friend could not qualify for a mortgage. He knows when he lists the house, he will have to abide by fair housing rules and not discriminate based on race.

Mr. Holley remembers when Crown Heights felt like it was “one hundred percent Black.” The area is now less than 50 percent Black. “That doesn’t bother me. It’s some of the people moving in that are problematic,” Mr. Holley said.

Not too long ago, he said, “I noticed a neighbor putting up something out front and I was curious. I went over to strike a conversation and before I could finish a sentence, he told me that he didn’t have any money.” Being mistaken for a panhandler by one of his new white neighbors sent a clear message about how the neighborhood was evolving. “I’ve lived here all my life. Only three other people on the block who’ve been here longer than I have,” he said.

Mr. Holley has made peace with the fact that his home likely won’t sell to a Black person, but he feels sad and a little guilty. “Once Black people move out, it’s hard for them to get back into the neighborhood because the gentrification completely prices them out.”

To allay the sense of guilt a Black homeowner might feel when selling their home in a gentrifying community, Dr. Faber noted first and foremost that “these longtime homeowners should be congratulated and appropriately compensated for these investments they made in these neighborhoods when white households were fleeing decades ago.”

He added that the problems associated with gentrification, “such as rising costs of living, increased police harassment, political and social displacement, aren’t caused by Black homeowners.” They are caused, he said, “by forces that move property, like speculative real estate purchasing, the consolidation of rental properties, zoning laws, mortgage markets. All of these things are far more influential than the individual homeowner.”

Despite a long history of Black homeownership in New York City, ever-rising real estate prices have made homes in the city inaccessible to many Black New Yorkers. According to a report on homeownership by the New York University Furman Center , New York City’s homeownership rate in 2014 was just 31 percent, less than half that of the national homeownership rate of 63 percent. Only 26 percent of Black households in the city-owned their homes, compared to 42 percent for white households, 39 percent for Asian households, and 15 percent for Hispanic households.

Jeremie Greer, the co-founder and co-executive director of Liberation in a Generation, a nonprofit focused on racial justice, believes that fair housing rules could be used to benefit Black homeowners and buyers. The Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Act , which requires localities to identify and address patterns of racial segregation outlawed under the Fair Housing Act of 1968, “was degraded during the Trump administration but has recently been restored, and can be used to buttress some of the challenges that Black and Brown home buyers are facing,” he said. For example, the act could be used to require communities to examine the legacy of redlining, he said, and “force local jurisdictions to provide remedies like down payment assistance and low-interest loans to Black and brown home buyers.”

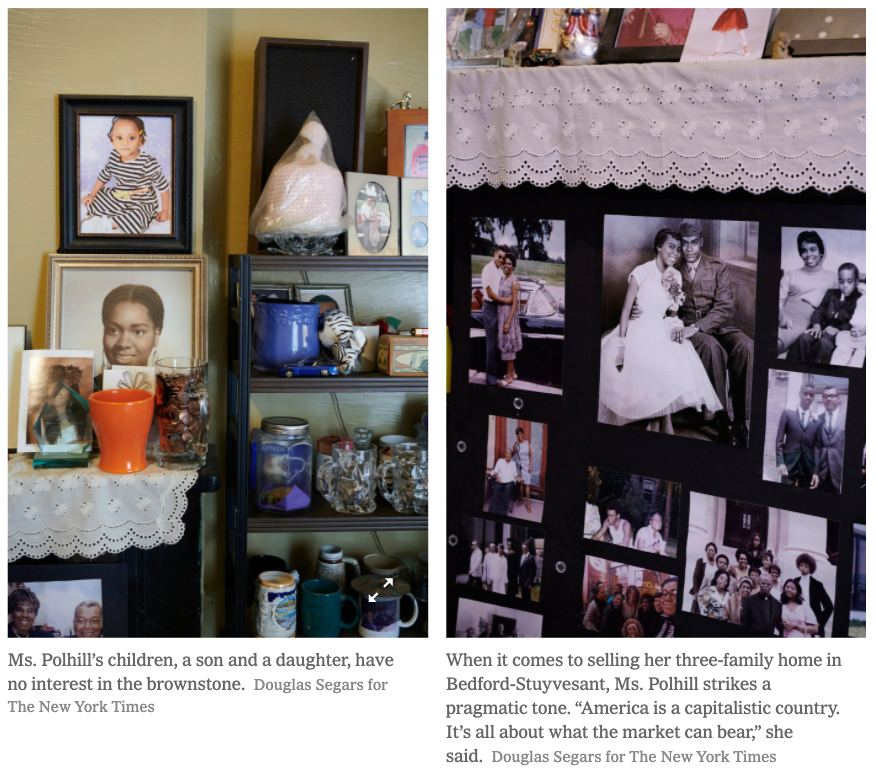

When it comes to selling her three-family home in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Evelyn Polhill, 89, strikes a pragmatic tone. “America is a capitalistic country. It’s all about what the market can bear,” she said. “If you’re selling your house, how are you being displaced? If you’re selling, you must be moving somewhere else. If you’re not factoring that in, then you’re telling yourself a lie. You’re not being honest.”

When Ms. Polhill and her husband bought their three-family Bedford-Stuyvesant house in 1958, 10 years before the Fair Housing Act was enacted, white families were fleeing the city and heading to the suburbs as Blacks moved in next door. The German couple who sold them the house left in a hurry. Now their home is highly desirable and out of reach for many Black people in her network. Like Mr. Holley’s son, Ms. Polhill’s children, a son who lives in Maryland and a daughter who has traveled the world through her airline job and who lives elsewhere in New York, have no interest in the brownstone.

“You know there was that song after World War I, ‘How ya you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree?’ You don’t want to come back to a place where people are doing the same old same old,” Ms. Polhill said. “My children have experienced other places and I don’t blame them for not wanting to come back.”

The emotional complexity of Black homeownership is familiar to Mark Winston Griffith, 58. As the director of Brooklyn Movement Center, he often reflects on the irony of working in a Black-led organization that works on building Black communities, when the very people in the community he is working to organize are disappearing.

“I’m lucky. I’m blessed. I’m trying to make sure that the generational benefits that I accrued I’m able to also pass on to other people who have not had that benefit. That’s where I’m coming from in terms of the future of this home,” said Mr. Griffith, who owns and lives in a brownstone that has been in his family for four generations. Not having his family inhabit its walls seems unthinkable.

Mr. Griffith bought the house from his father who gave him a gift of equity, allowing Mr. Griffith to pay below market value for the house. It was the only way he could afford it. Although he currently has no intention of selling, he said, “Anyone who has lived in New York has talked about leaving at some point.” He can’t control what happens, but he hopes the house will go to his two sons.

It’s difficult not to be sad at the disappearance of a particular kind of history and neighborhood legacy, Mr. Griffith said.

“As a student of communities, I know that this is what neighborhoods do,” he said. “They change. And so there’s a part of me that looks at it with an understanding that neighborhoods aren’t static, nor do you want them to be.”

When the time comes for him to sell his home, if neither of his sons wants the house, he said he can hope that it sells to a Black family or will be used for some community purpose.

“All I can do is make sure that there’s a place for Black people, for my family, and it’s a healthy and thriving neighborhood,” he said.

CREDITS: Jacquelynn Kerubo / The New York Times

The post What Gentrification Means for Black Homeowners appeared first on National Association of Real Estate Brokers.